Interview with Mo

FILMMAKER STORIES

Storyworld Name

Ethiopian Treasure

Year of Production

2022

Location

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

How did you first come across Asalif and his story?

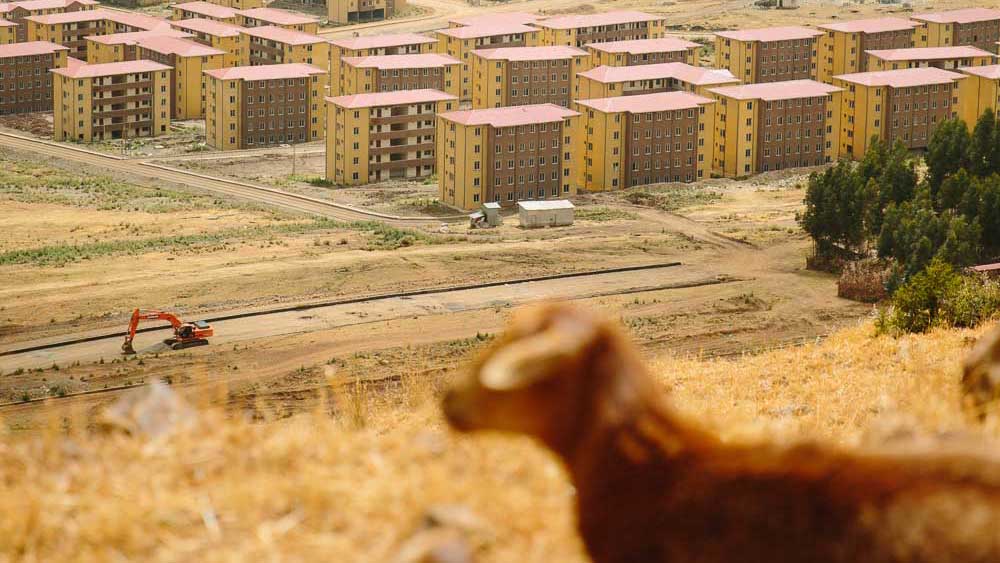

I had been working in Ethiopia for a while on different projects. I had good friends in the country; I was becoming fascinated by the culture and the ways in which it’s been very resistant to colonialism. In fact, for 100 years foreigners couldn’t come to Ethiopia. But yet, one time I was flying in for a shoot and saw this massive condominium taking shape on the outskirts of Addis Ababa and I was like OK, I have never seen this kind of thing in Ethiopia. And it looks very European. And that just kind of sparked it. I had met a translator through a friend of mine so I extended my trip for two weeks and just hung out in the area of this condominium.

When I got home I realised I really wanted to make a film about this place so I got a little bit of funding to go back. That’s when I met Asalif- I was just sitting in one of these unfinished courtyards with my translator and he poked his head out from behind a building. We invited him over to speak with us and when we would ask him questions he would answer in a kind of fable. So, like, he had been displaced by the condo but we didn’t know that so we asked him where he lived. And instead of telling us he’d been displaced he said something like, ‘I’m like a bird in the night, I fly off into the sky and that’s where I sleep’. So I was like, ‘who is this?’. I’ve filmed all kinds of people but I’ve never felt this enigmatic kind of energy. So I asked if I could film him talking to my translator and right away he was very camera friendly and didn’t care that I was filming.

I went to meet his mum and decided that he could be our guide through this story of rapid development and the annuls of that. Really, he was situated in the perfect place to explore this because he was on the edge of this condo but so connected to the farmer, traditional way of life.

It’s so amazing to hear how the process unfolded. So I guess the story came out of a love for Ethiopia paired with the shock of never seeing that development before…

To what extent do you think he was aware of that social tension and change going on around him?

It’s really important to hear the way you take responsibility for the impact your presence and your making of the film had on Asalif and his perspective on the world around him. Do you feel that creating the film has supported Asalif and his community in any way?

I agree. It’s amazing that this story is also now coming to younger audiences through Lyfta. What drew you to want to work with us?

Yes. It’s incredible to be a part of facilitating that connection between people in such different contexts. And overcoming those geographical barriers just by listening to someone’s story and watching the ways they play and interact with people. How did you decide on the story you were going to tell in the Lyfta cut of your film?

How did you find incorporating the 360 element to your story?

I really liked it! It was my first time but it was easier than I expected. It was really fun to set something up and watch life unfold and allow it to keep unfolding unobstructed. I try to do this with my films anyway! And the other thing that was cool is that sometimes when I’d show the film to people they would be like, ‘I don’t know what Addis looks like’. So it was amazing to have the opportunity to show the different parts of it.